ABOUT THE DTR

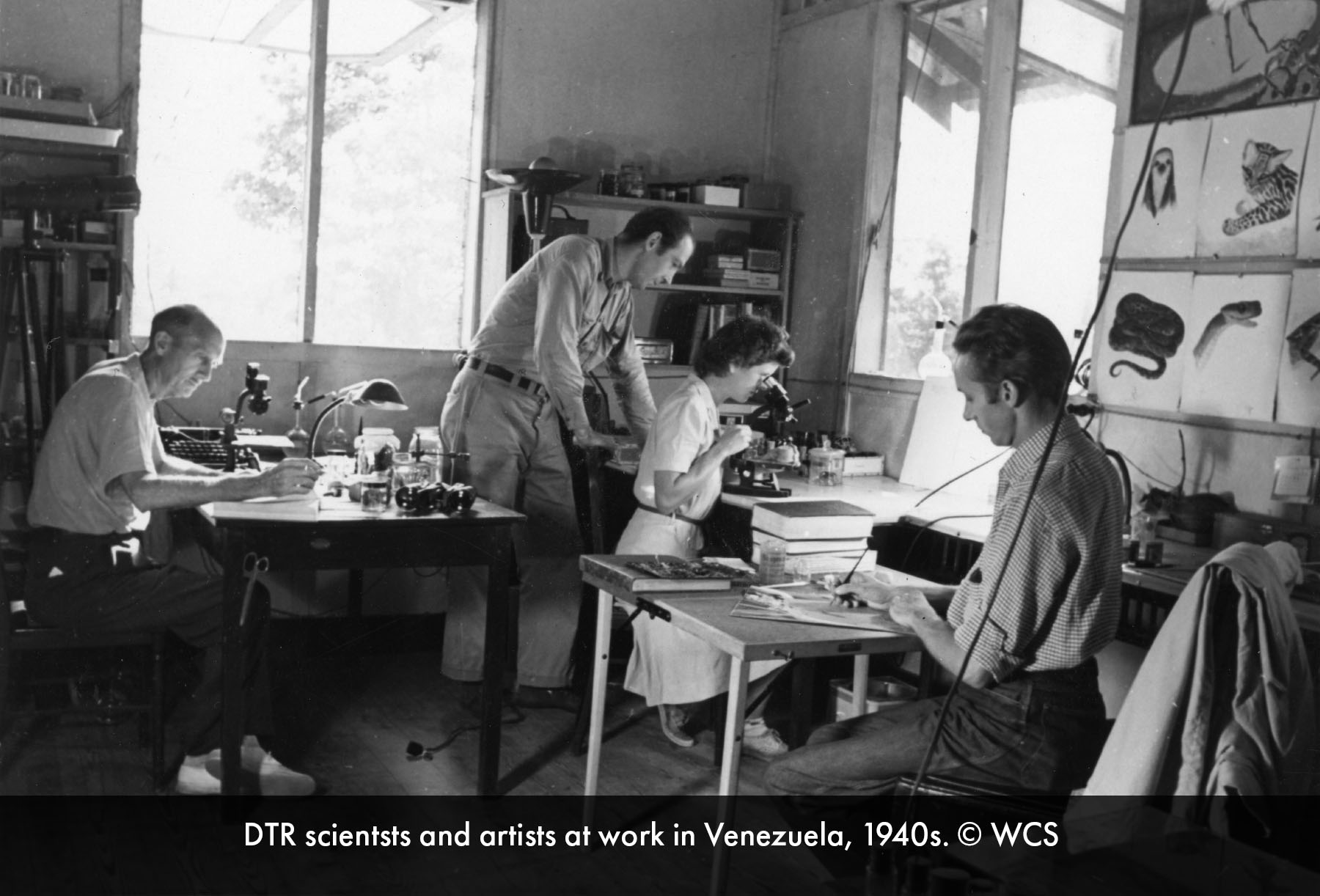

Between 1916 and 1965, WCS’s Department of Tropical Research (DTR) conducted dozens of ecological expeditions across tropical terrestrial and marine locales. The DTR was led by William Beebe (1877-1962), the Bronx Zoo’s first Curator of Birds. During his career, Beebe became increasingly interested in studying animals in their natural environments. Seeking to perform what is now regarded as ecological research, Beebe began a field station in 1916 in what was then British Guiana. He soon officially formed WCS’s DTR, a team of field artists and scientists dedicated to studying tropical wildlife and its habitats. Although Beebe’s name is unfamiliar to most today, he was a celebrity scientist in his time. The DTR’s expeditions were covered by the popular press, Beebe’s accounts were bestsellers, and he and the DTR staff published hundreds of articles for both scientists and the general public.

Central to the DTR’s profound influence on both technical and popular audiences was its use of art as a tool for exploring and documenting ecology. Within the DTR, the artists were not simply decorators of the scientists’ writings; instead, they were essential communicators of information about ecological relationships. DTR staff artists produced over 3,300 illustrations—over 2,200 of which are present in this online collection—ranging from depictions of single specimens to complex narrative images that show where and how animals lived. At a time when photography could not adequately capture movement and color, DTR artists constructed visualizations of natural environments that had been difficult or impossible to access, let alone record.

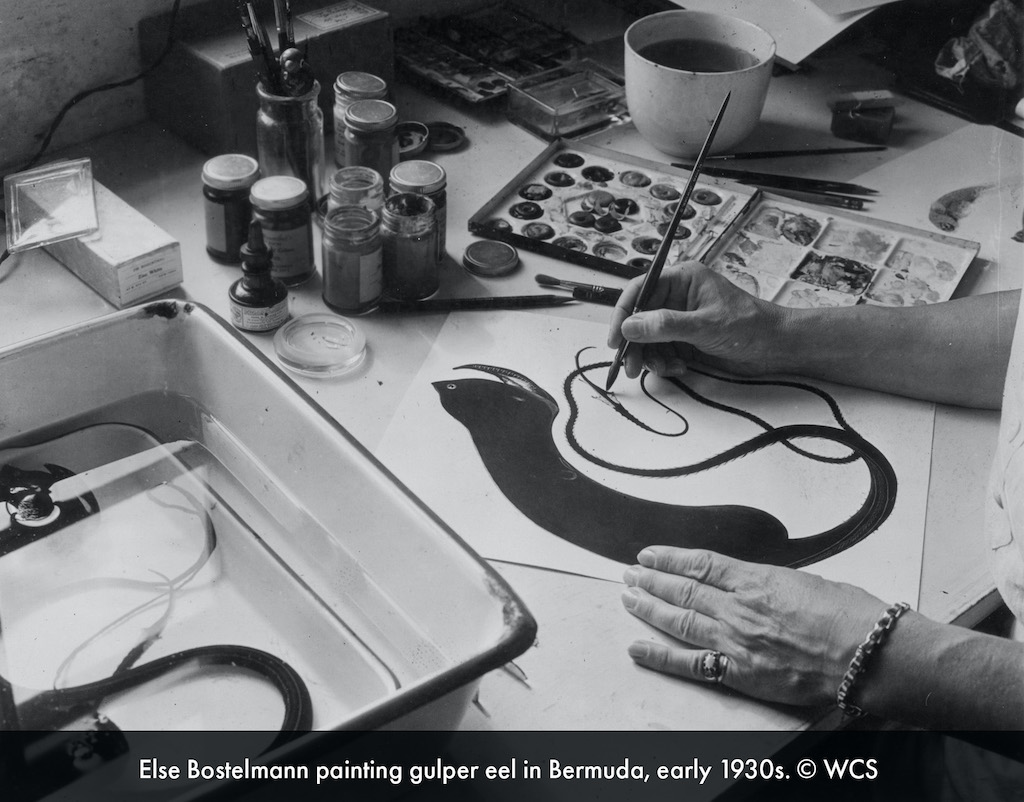

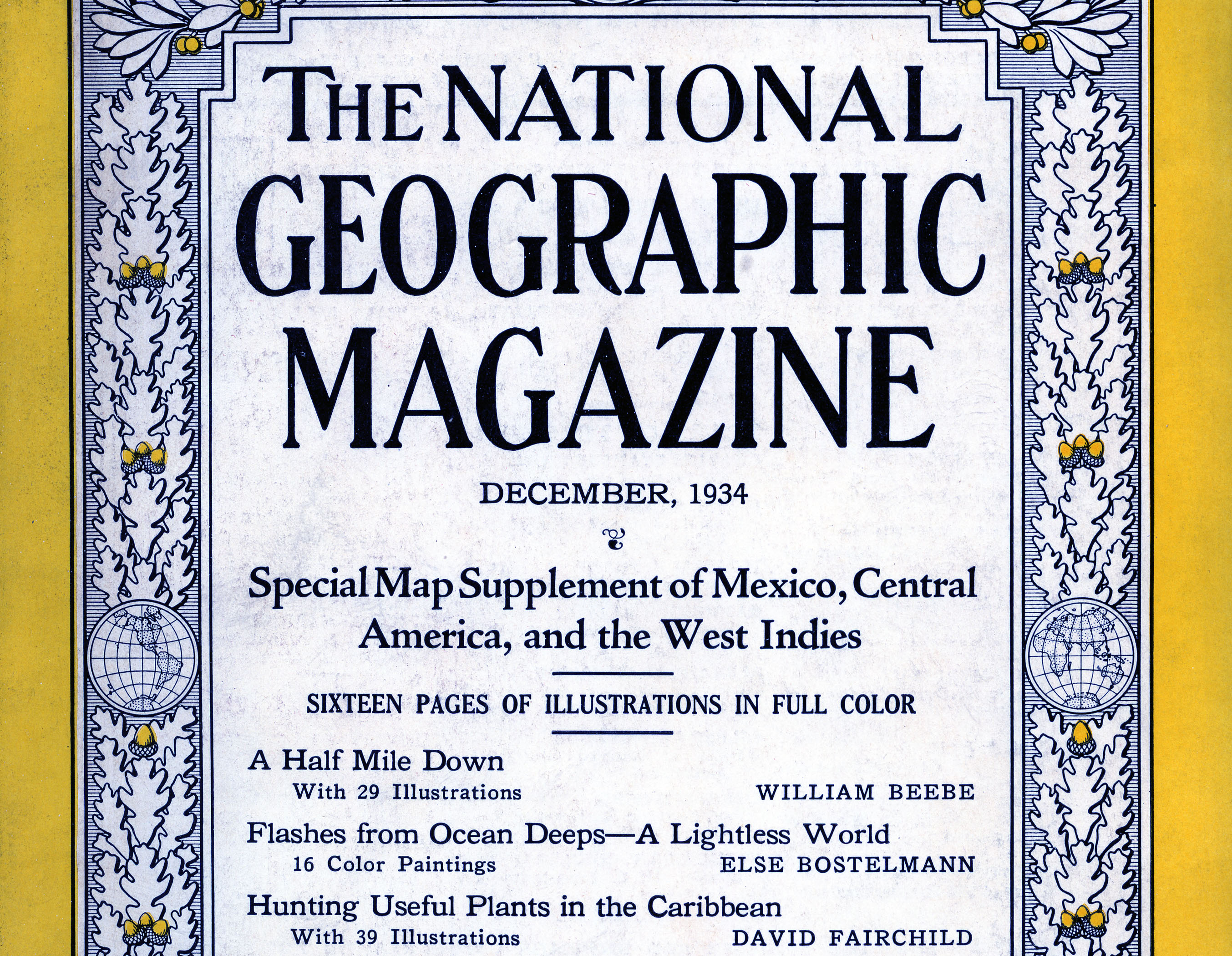

DTR artists often worked from collected specimens, painstakingly illustrating the minutiae of shape, color, and patterning. They also worked in the field, perching among tropical forests with drawing paper in their laps or donning diving helmets and strapping zinc tablets to their swimsuits in order to draw underwater. In some cases, DTR artists had to rely on Beebe’s verbal descriptions and notes to visually reconstruct environments and animals. During the record-setting Bathysphere descents in the 1930s, for instance, Beebe spent his time in the submersible describing everything he could about the marine life he was observing through its quartz window into the telephone transmitter that ran to the ship above him, where DTR scientist Gloria Hollister transcribed Beebe’s dictation. In turn, DTR artist Else Bostelmann relied on these notes together with additional descriptions from Beebe to create illustrations of deep-sea creatures she had not observed herself.

Dozens of the illustrations were used in technical publications, but they reached a wider audience through their inclusion in popular publications, including articles in National Geographic, the Bulletin of the New York Zoological Society (and its successor, Animal Kingdom), and the New York Times, as well as many of Beebe’s bestselling books. Indeed, Beebe and the DTR made extraordinary efforts to reach audiences beyond scientists. In addition to publishing popular articles and books, they wowed viewers across the country with depictions of their jungle research and marine encounters in live lectures and exhibitions at such venues as the Bronx Zoo and the American Museum of Natural History. In these popular forms, from articles to exhibitions, the illustrations were central to shaping US viewers' understandings of tropical regions and the wildlife that inhabit them.

During its nearly fifty-year existence, over a dozen artists participated in the DTR expeditions. They include Toshio Asaeda, Harriet Bennett (later Strandberg), Else Bostelmann, Douglas Boyden, Gilbert Broking, John Cody, Isabel Cooper (later Mahaffie), Donald Dickerman, Julie C. Emsley, Dwight Franklin, Frances Waite Gibson, E. J. Geske, Kenneth Gosner, Rachel Hartley, Paul G. Howes, Llewellyn Miller, Laura Schlageter, George Swanson, Anna Taylor, Elswyth Thane, Helen Damrosch Tee-Van, and Ezra Winter. The majority of these artists are known to be represented in this online collection. See the Using the Digital Collection page for more information.

Beyond the artists and scientists mentioned here, there were dozens of local people who contributed to this production of scientific knowledge. Although the DTR relied on the knowledge, expertise, and physical labor of people who inhabited the countries in which they worked, those individuals went largely uncredited by the DTR. Today, while we have identified the names of DTR artists and scientists on this site, we also recognize the critical work of the many whose names are unknown to us now.

Portions of the text above come from the introduction to the exhibition catalog Exploratory Works: Drawings from the Department of Tropical Research Field Expeditions (The Drawing Center, 2017), written by curators Mark Dion, Katherine McLeod, and Madeleine Thompson. For general information on the DTR’s history, see the Historical Note for WCS Archives Collection 1005A. Additional details can be found in the WCS Annual Reports, which include annual reports from the Department of Tropical Research between 1916 and 1965.